︎ technical info

Interdisciplinary project

For solo exhibition Wozu Poesie?, Akademie der Künste Standort Hanseatenweg, Halle 3, Berlin, Germany

Concept: Sergey Shabohin

Project director: Dr. Thomas Wohlfahrt

Project leader: Alexander Filyuta

Project coordination: Heide Schürmeier

Interdisciplinary project

For solo exhibition Wozu Poesie?, Akademie der Künste Standort Hanseatenweg, Halle 3, Berlin, Germany

Concept: Sergey Shabohin

Project director: Dr. Thomas Wohlfahrt

Project leader: Alexander Filyuta

Project coordination: Heide Schürmeier

Interdisciplinary project

Wozu Poesie?,

Akademie der Künste,

Berlin, Germany,

2013

Wozu Poesie?,

Akademie der Künste,

Berlin, Germany,

2013

47 Poets from 47 European countries share their thoughts on the question «what’s the point of poetry?» in 47 photos. They’ve created slogans that comment on the state of culture and society in their countries while also keeping poetry in focus. This June at the Berlin Poetry Festival (poesiefestival berlin), their very diverse poetic messages and points of view will be assembled in an exhibition. The photos are demonstrations and acts of solidarity at the same time. There has never been such an exhibition before. It offers the unique opportunity of bringing the variety of European voices and moods together in one place.

47 photos:

+ info: country, poet, translation of the slogan into English,

the poet's comment about the chosen place for the photo

and the name of the photographer

+ info: country, poet, translation of the slogan into English,

the poet's comment about the chosen place for the photo

and the name of the photographer

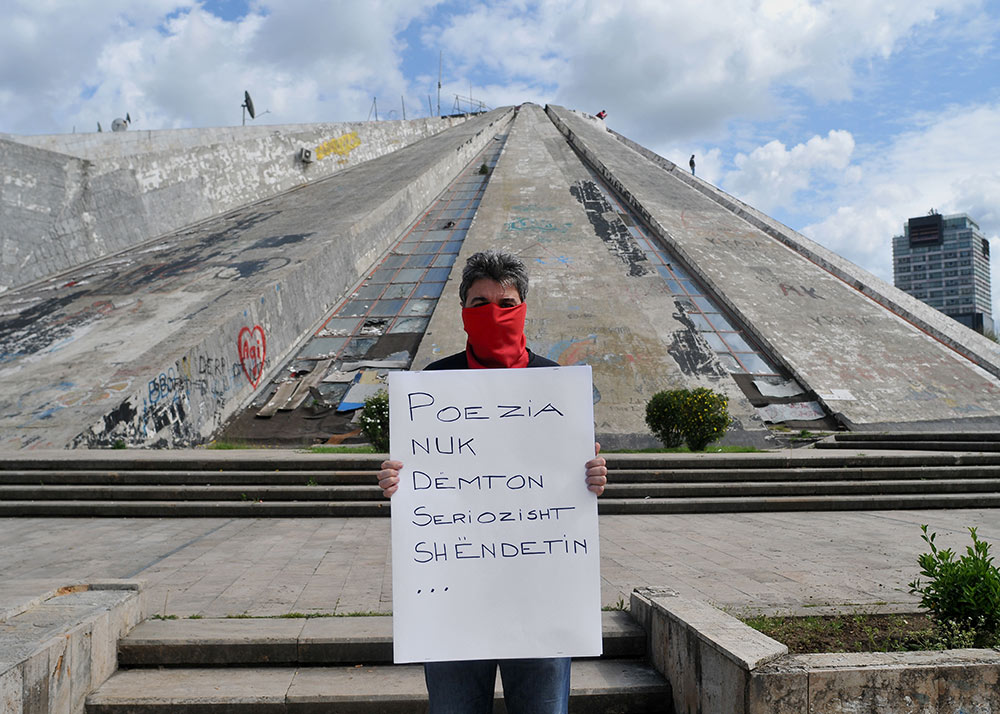

1. Albania: Arian Leka

![]()

Poetry is not seriously harmful to your health …

Photo: This photo was taken in front of the Pyramid of Tirana, the former museum of the Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha.

Photo by: Roland Tasho

2. Andorra: Teresa Colom

![]()

Listen in close. / Truth is too quiet / for reason to answer it.

Photo: This photo was taken in the Vall del Madriu (Madriu Valley), a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It offers a microcosmic perspective of the ways people have exploited the resources of the high Pyrenees over many millennia. For me, it symbolises humans, human history, nature, sky, earth, questions, answers, survival and resistance.

Photo by: Xavier Colom

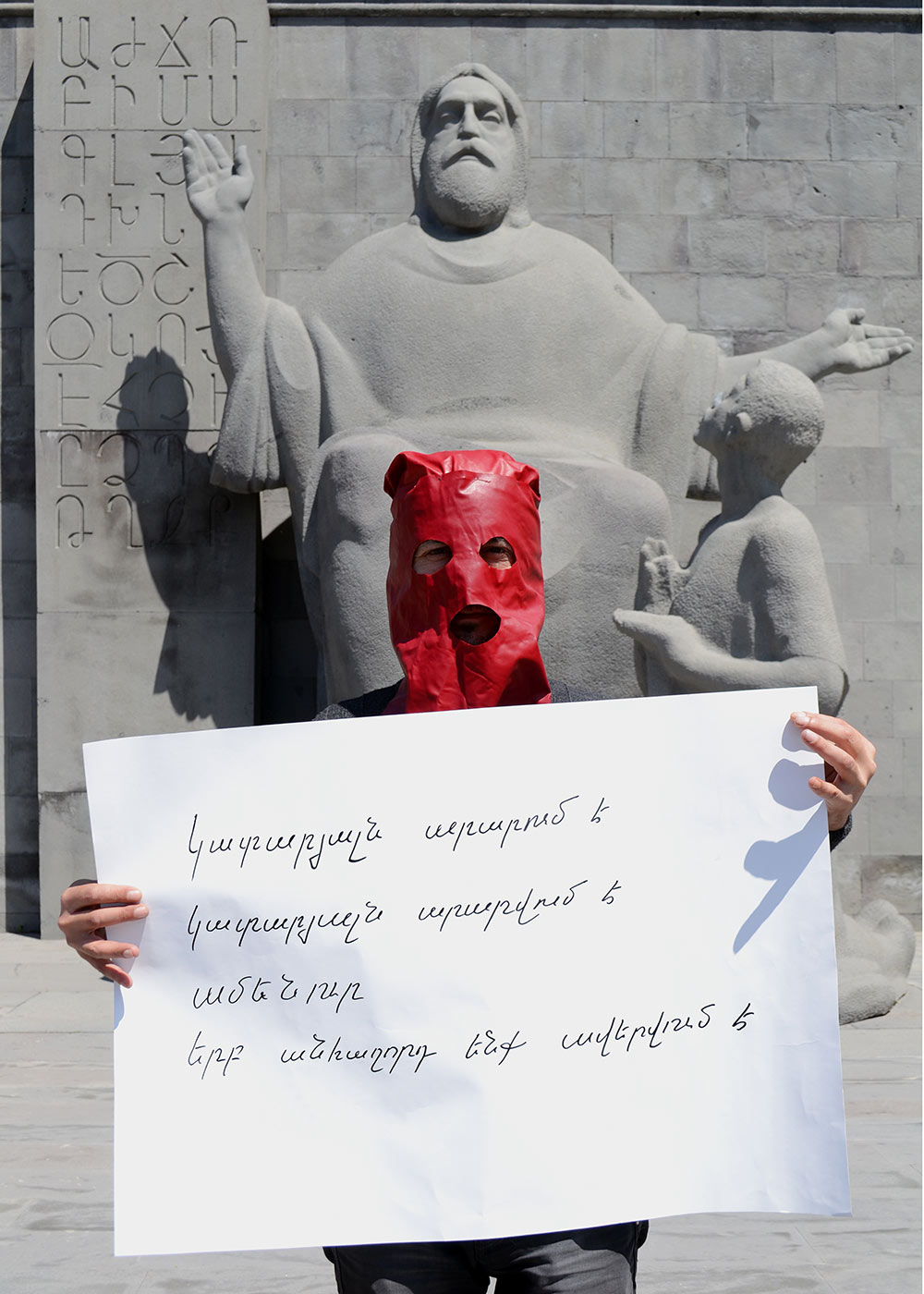

3. Armenia: Gevorg Gilants

![]()

Perfection creates / Perfection is created / Everywhere / Wher there’s discord / There’s decay

Photo: This photo features the Armenian alphabet and its creator, Mesrop Mashtots. According to official sources, one language disappears every week. Language is perfection. If we remain indifferent and do not read, write or use a language in any way, the language dies. Unlike the few major languages, the risk of death hovers over all small languages.

Photo by: Avetis Avetisyan

4. Austria: Sophie Reyer

![]()

WHAT’S THE POINT OF WORDS? / politic is violence./ language WITHOUT BORDERS

Photo: Poetry is a form of resistance. The view from above is intended to symbolize the bird’s eye view that language takes: a being that looks at itself, exposes itself and is simultaneously stared at. The dog in the background. The animal in us? The mask: enviable, this anonymity of the artist in the Middle Ages.

Photo by: Lisa Schmermer

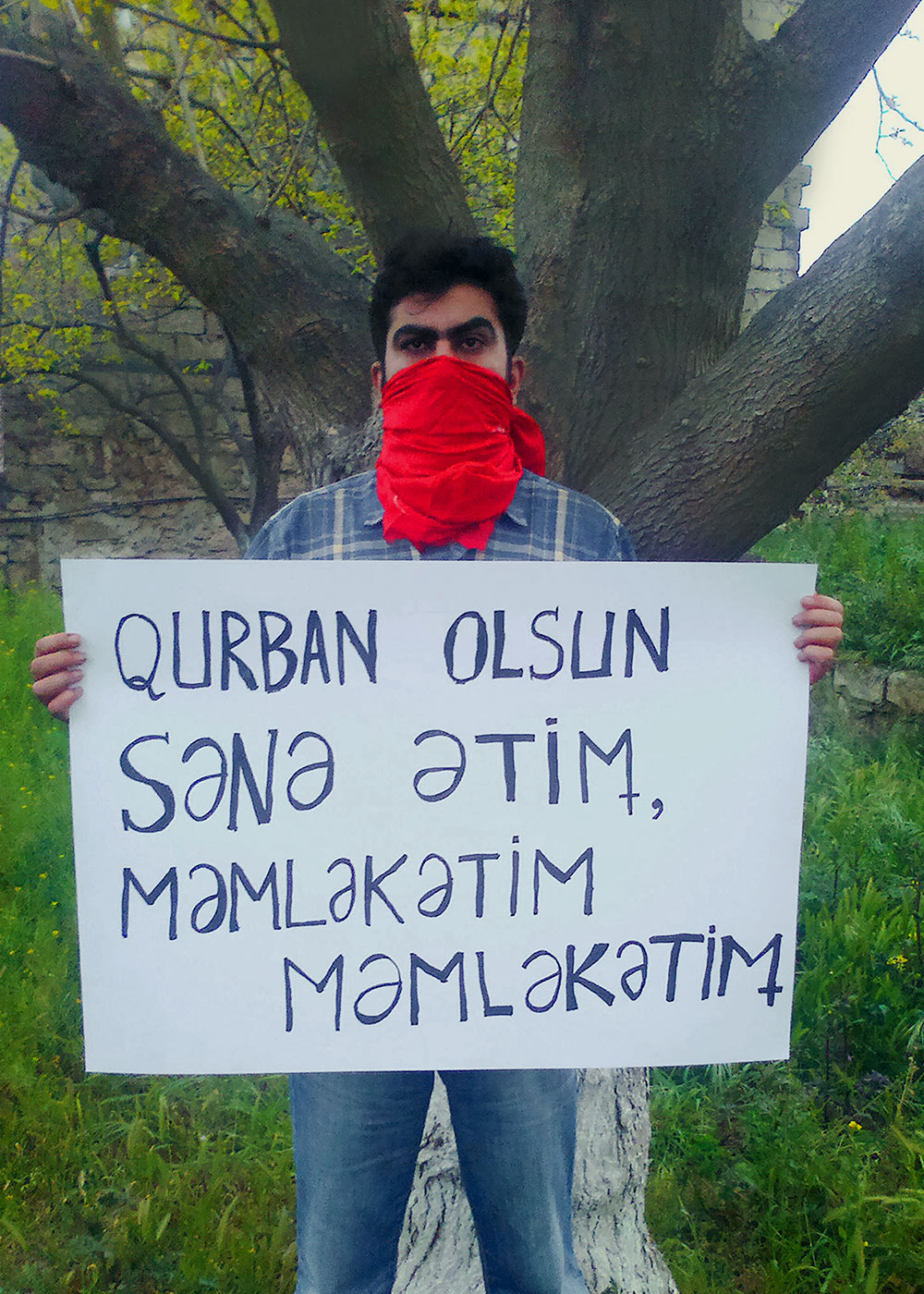

5. Azerbaijan: Nijat Mammadov

![]()

Oh homeland, oh homeland, / I sacrifice to you my flesh!

Photo: This photo was taken in my garden in front of a mulberry tree. This tree, which shares my age, is charged with meaning. It symbolises my little home (my homeland) as well as the immeas- urable country that the world of mythology, poetry, and culture has become to me.

Photo by: Ulvi Dann

6. Belarus: Volha Hapeyeva

![]()

My civilized society abuses women / then it wipes its hands / and reads poetry

Photo: Behind the poet to the right is the National Library of Belarus. In the distance is a large inscription: Flourish, my homeland Belarus!

Photo by: Sergey Shabohin

7. Belgium: Xavier Roelens

![]()

Never be too lazy for a thousand words. / Make them happen.

Photo: This photo was taken at the French-Belgian border. Rekkem is on the left. Another small, nameless town is on the right. I could probably use a thousand words to describe what it means to live on the border, but I’ll keep it to this short comment.

Photo by: Joselyn Roelens

8. Bosnia and Herzegovina: Senadin Musabegović

![]()

Through visibility poetry touches the invisible

Photo: In the background of this photo is the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It has been closed since the fall of 2012 due to its unresolved legal status and constant problems with the financing of the operating costs.

Photo by: AsjaM

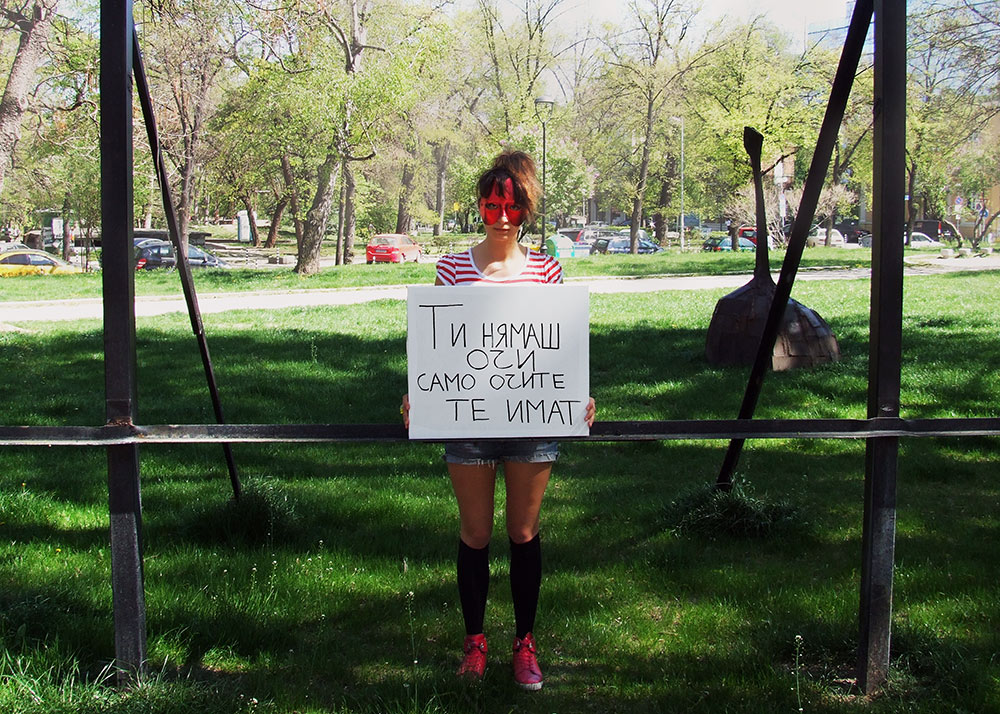

9. Bulgaria: Mina Stoyanova

![]()

You have no eyes, only the eyes have you

Photo: A rear view of the National Library in Sofia with a missing billboard and an empty fountain.

Photo by: Yassen Vassilev

10. Croatia: Ivan Herceg

![]()

Who will I surrender to? And you? / How much space are we going / to leave inside for one another / and how much of us will remain?

Photo: This photo was taken on Ivan Lucic Sreet in Zagreb in front of the Faculty of Philosophy, which is very important place for freedom and democracy in Croatia.

Photo by: Goran Cizmesija

11. Cyprus: Constantinos Papageorgiou

![]()

It reflects in it’s kaleidoscope / the effect of life on people

Photo: The photo is taken a few kilometres away from home, next to the sea that makes me feel like home too. The sea gives me the illusion of infinity; the waves sort the chaos inside me; the ships offer me the alternative of drifting away; the red mask masquerades my uniqueness. In such a context, poetry becomes my medium of expression.

Photo by: Tommy Sepasdar

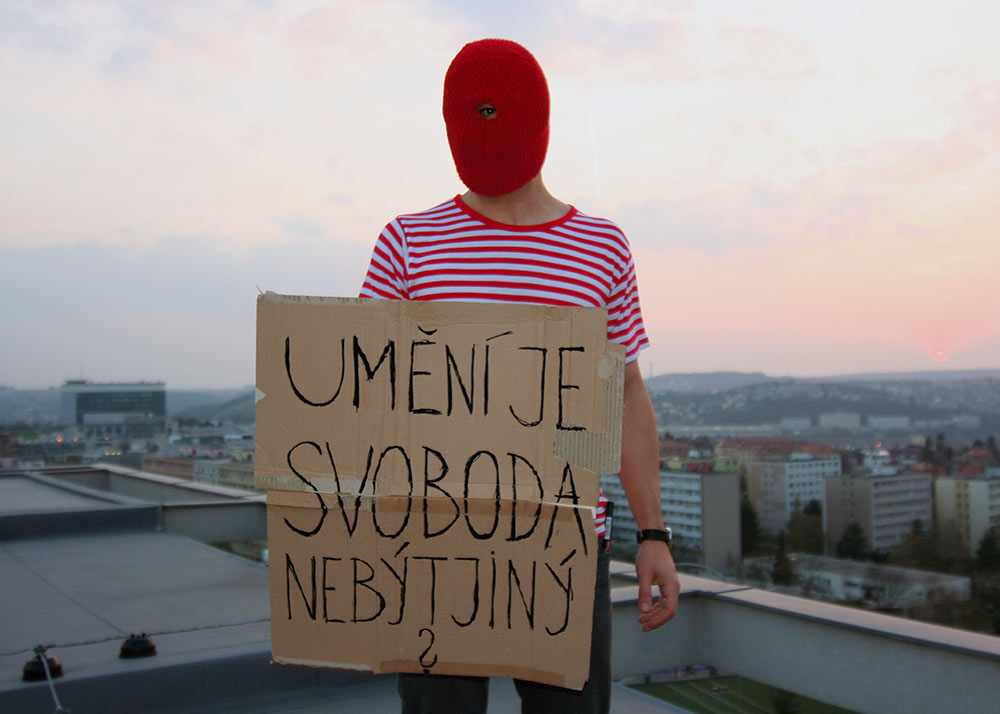

12. Czech Republic: Ondřej Buddeus

![]()

Is art the freedom not to be different?

Photo: This image is taken from the roof of our prefab. The roof was originally intended to serve as an open community space for its residents. Prefabricated buildings are often used as a symbol of uniformity. However, each unit has a life of its own. It is an organism. For art and poetry, diversity is often an axiom – particularly the diversity of producers. Thus, they often end up more uniform than expected. Ideology of originality? Each doxa has a periphery, that of the paradoxal. Therefore, I have no clear statement on my cardboard, but only a nonsensical question. Access to the roof has been closed off for years. Is the question on the sign also a key question? This question is pathos-laden, a prefab is not.

Photo by: Hana Buddeus

13. Denmark: Martin Glaz Serup

![]()

To think about a place / is to think about something else

Photo: In the background of this photo is the Nikolaj Kirke, a former church in the very heart of Copenhagen, close to the parliament and the stock exchange. Today it is an international contemporary art center.

Photo by: Pernille Arvedsen

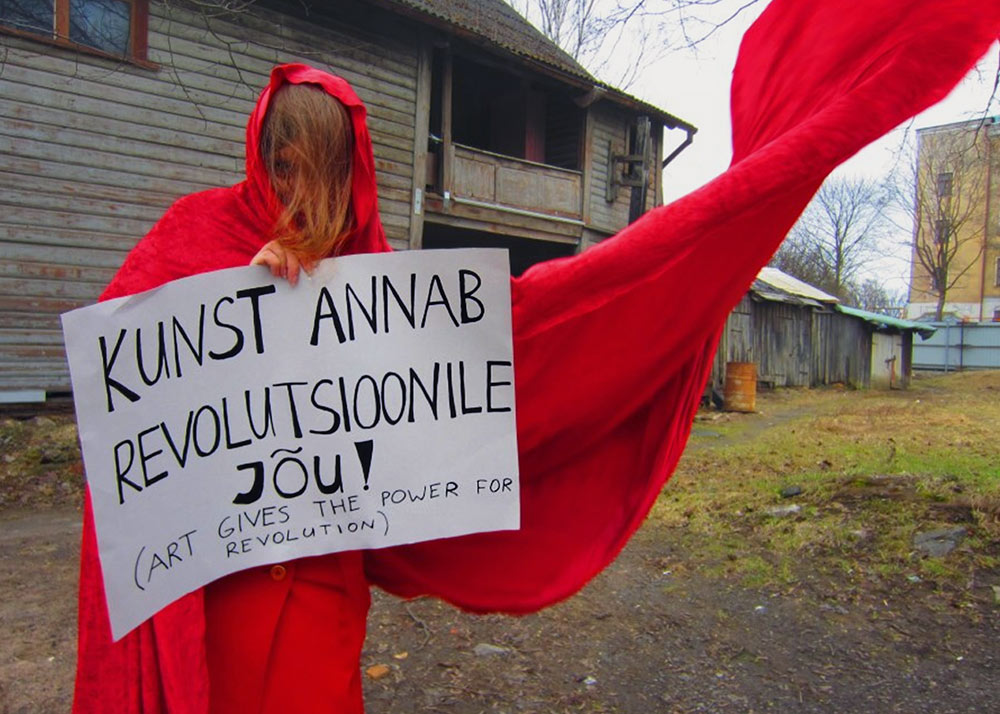

14. Estonia: Joanna Ellmann

![]()

Art gives the power for revolution!

Photo: The location demonstrates how the old world is collapsing and how the new one that is coming will also collapse because the old one is not yet fixed. The world must be renewed without denying the old one, and new roads must be established without suppressing the existing ones. A revolution is essential in order for the world to learn to value different layers of society. The photo was taken on Filosoofi Street (Philosophy Street) in the Estonian City of Tartu. The name of the street is no coincidence.

Photo by: Janis Alver

15. Finland: Harri Hertell

![]()

Read your poems on the street / you can earn enough / for a kebab with fries

Photo: This photo was taken in an alley near my childhood home. There used to be graffiti all along the walls, they got cleaned away a long time ago. At the end of the alley there was a schoolyard where my friends and I used to hang out as teens. Once I tossed an entire deck of cards in the air and boasted that I could guess the rank and suite of any of them as soon as they landed. The first one I picked up was the nine of clubs, which was exactly what I predicted.

Photo by: Sara Vallioja-Hertell

Poetry is not seriously harmful to your health …

Photo: This photo was taken in front of the Pyramid of Tirana, the former museum of the Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha.

Photo by: Roland Tasho

2. Andorra: Teresa Colom

Listen in close. / Truth is too quiet / for reason to answer it.

Photo: This photo was taken in the Vall del Madriu (Madriu Valley), a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It offers a microcosmic perspective of the ways people have exploited the resources of the high Pyrenees over many millennia. For me, it symbolises humans, human history, nature, sky, earth, questions, answers, survival and resistance.

Photo by: Xavier Colom

3. Armenia: Gevorg Gilants

Perfection creates / Perfection is created / Everywhere / Wher there’s discord / There’s decay

Photo: This photo features the Armenian alphabet and its creator, Mesrop Mashtots. According to official sources, one language disappears every week. Language is perfection. If we remain indifferent and do not read, write or use a language in any way, the language dies. Unlike the few major languages, the risk of death hovers over all small languages.

Photo by: Avetis Avetisyan

4. Austria: Sophie Reyer

WHAT’S THE POINT OF WORDS? / politic is violence./ language WITHOUT BORDERS

Photo: Poetry is a form of resistance. The view from above is intended to symbolize the bird’s eye view that language takes: a being that looks at itself, exposes itself and is simultaneously stared at. The dog in the background. The animal in us? The mask: enviable, this anonymity of the artist in the Middle Ages.

Photo by: Lisa Schmermer

5. Azerbaijan: Nijat Mammadov

Oh homeland, oh homeland, / I sacrifice to you my flesh!

Photo: This photo was taken in my garden in front of a mulberry tree. This tree, which shares my age, is charged with meaning. It symbolises my little home (my homeland) as well as the immeas- urable country that the world of mythology, poetry, and culture has become to me.

Photo by: Ulvi Dann

6. Belarus: Volha Hapeyeva

My civilized society abuses women / then it wipes its hands / and reads poetry

Photo: Behind the poet to the right is the National Library of Belarus. In the distance is a large inscription: Flourish, my homeland Belarus!

Photo by: Sergey Shabohin

7. Belgium: Xavier Roelens

Never be too lazy for a thousand words. / Make them happen.

Photo: This photo was taken at the French-Belgian border. Rekkem is on the left. Another small, nameless town is on the right. I could probably use a thousand words to describe what it means to live on the border, but I’ll keep it to this short comment.

Photo by: Joselyn Roelens

8. Bosnia and Herzegovina: Senadin Musabegović

Through visibility poetry touches the invisible

Photo: In the background of this photo is the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It has been closed since the fall of 2012 due to its unresolved legal status and constant problems with the financing of the operating costs.

Photo by: AsjaM

9. Bulgaria: Mina Stoyanova

You have no eyes, only the eyes have you

Photo: A rear view of the National Library in Sofia with a missing billboard and an empty fountain.

Photo by: Yassen Vassilev

10. Croatia: Ivan Herceg

Who will I surrender to? And you? / How much space are we going / to leave inside for one another / and how much of us will remain?

Photo: This photo was taken on Ivan Lucic Sreet in Zagreb in front of the Faculty of Philosophy, which is very important place for freedom and democracy in Croatia.

Photo by: Goran Cizmesija

11. Cyprus: Constantinos Papageorgiou

It reflects in it’s kaleidoscope / the effect of life on people

Photo: The photo is taken a few kilometres away from home, next to the sea that makes me feel like home too. The sea gives me the illusion of infinity; the waves sort the chaos inside me; the ships offer me the alternative of drifting away; the red mask masquerades my uniqueness. In such a context, poetry becomes my medium of expression.

Photo by: Tommy Sepasdar

12. Czech Republic: Ondřej Buddeus

Is art the freedom not to be different?

Photo: This image is taken from the roof of our prefab. The roof was originally intended to serve as an open community space for its residents. Prefabricated buildings are often used as a symbol of uniformity. However, each unit has a life of its own. It is an organism. For art and poetry, diversity is often an axiom – particularly the diversity of producers. Thus, they often end up more uniform than expected. Ideology of originality? Each doxa has a periphery, that of the paradoxal. Therefore, I have no clear statement on my cardboard, but only a nonsensical question. Access to the roof has been closed off for years. Is the question on the sign also a key question? This question is pathos-laden, a prefab is not.

Photo by: Hana Buddeus

13. Denmark: Martin Glaz Serup

To think about a place / is to think about something else

Photo: In the background of this photo is the Nikolaj Kirke, a former church in the very heart of Copenhagen, close to the parliament and the stock exchange. Today it is an international contemporary art center.

Photo by: Pernille Arvedsen

14. Estonia: Joanna Ellmann

Art gives the power for revolution!

Photo: The location demonstrates how the old world is collapsing and how the new one that is coming will also collapse because the old one is not yet fixed. The world must be renewed without denying the old one, and new roads must be established without suppressing the existing ones. A revolution is essential in order for the world to learn to value different layers of society. The photo was taken on Filosoofi Street (Philosophy Street) in the Estonian City of Tartu. The name of the street is no coincidence.

Photo by: Janis Alver

15. Finland: Harri Hertell

Read your poems on the street / you can earn enough / for a kebab with fries

Photo: This photo was taken in an alley near my childhood home. There used to be graffiti all along the walls, they got cleaned away a long time ago. At the end of the alley there was a schoolyard where my friends and I used to hang out as teens. Once I tossed an entire deck of cards in the air and boasted that I could guess the rank and suite of any of them as soon as they landed. The first one I picked up was the nine of clubs, which was exactly what I predicted.

Photo by: Sara Vallioja-Hertell

16. France: Fabienne Yvert

![]()

Poets / Your anthropometric passports

Photo: The photo was taken in Marseille, where I live, in close proximity of the port, in a very open and simultaneously very closed and heavily-proctected place: Esplanade du J4.

Photo by: Sarah Wiechers

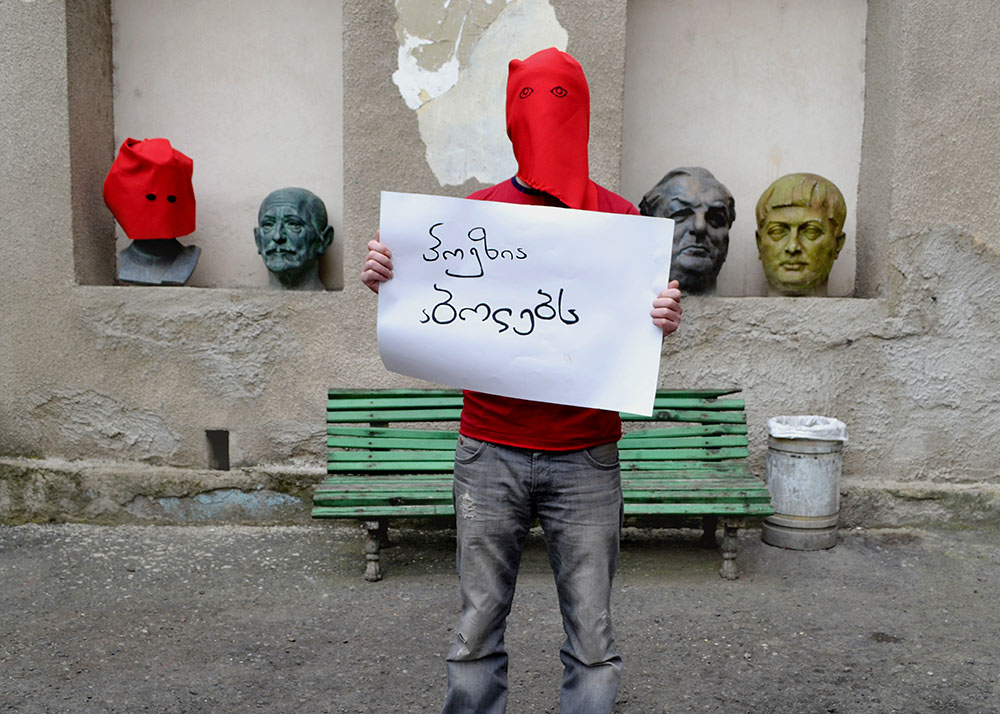

17. Georgia: Paata Shamugia

![]()

Poetry gets you stoned

Photo: This photo of me, surrounded with the busts of famous Georgian authors, was taken in the yard of the Museum of Literature.

Photo by: Nino Gogua

18. Germany: Sabine Scho

![]()

To tap the planet

Photo: This photo was taken on Teufelsberg, a mountain of rubble in Berlin, in front of the ruins of an American communications interception station, which were part of the global spy network Echelon during the Cold War.

Photo by: Matthias Holtmann

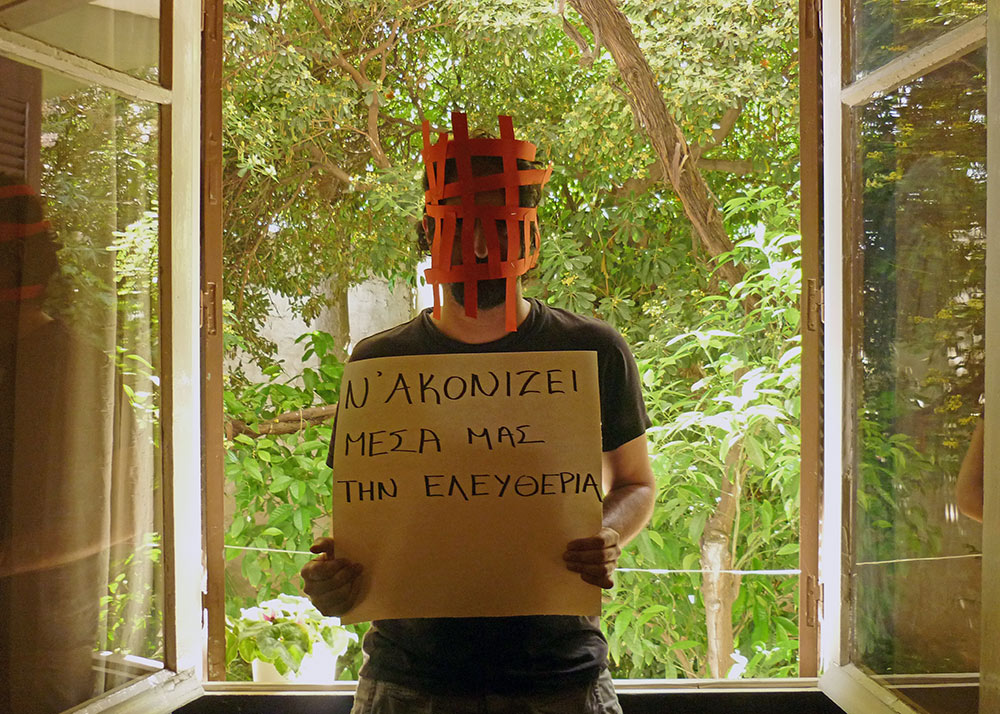

19. Greece: Yannis Stiggas

![]()

To sharpen freedom inside us

Photo: The mask is like a cage. It reminds me of The Man in the Iron Mask and is strongly related to the verse on the cardboard. This photo was taken in my apartment. It has only one window, the only source of light. All the other corners are quite dark.

Photo by: Eleni Chrysopoulou

20. Hungary: Petra Szőcs

![]()

To stop you forgetting

Photo: I once lived nearby for a winter.

Photo by: Nagy Botond

21. Ireland: Máighréad Medbh

![]()

Law rules / Poetry appeals

Photo by: Ayoma Bowe & David Maybury, Poetry Ireland

22. Iceland: Kristín Ómarsdóttir

![]()

Butter, buns, powder / polar bears and poets, endangered?

Photo: This photo was taken in the downtown area of Reykjavík, the main shopping artery of the city. In the background are hotels and a fast food restaurant. On the right is a model of a polar bear and its cub, shackled together to a souvenir shop.

Photo by: Davíd Kjartan Gestsson

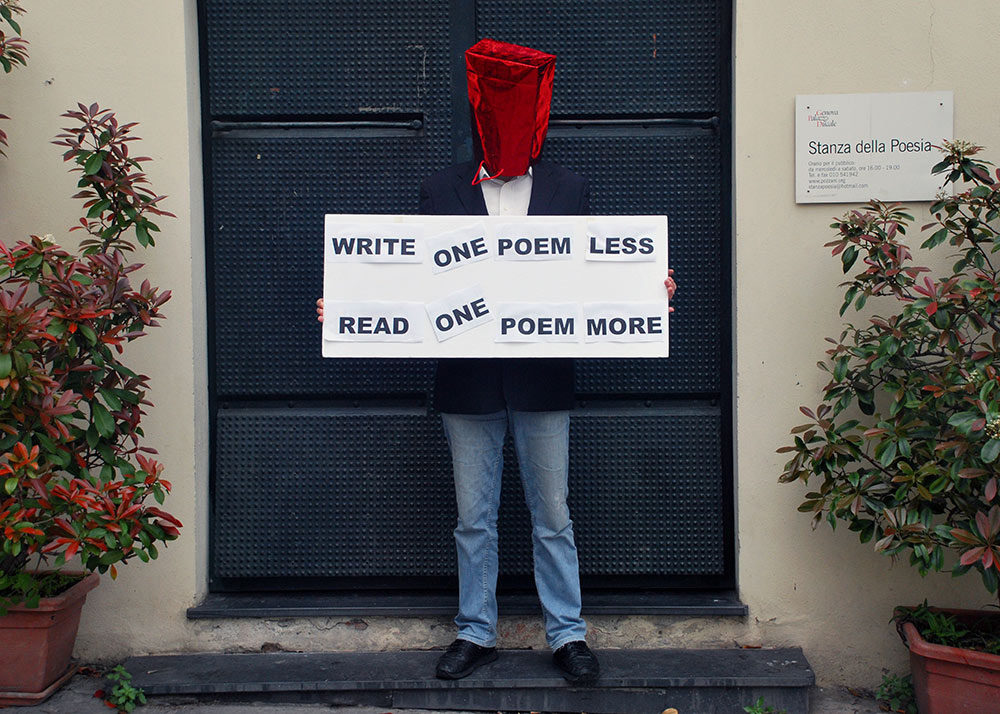

23. Italy: Claudio Pozzani

![]()

Write one poem less, read one poem more

Photo: The location of this photo is the Palazzo Ducale, the most important historical building in Genua, where I have been organizing the Genua International Poetry Festival since 1995. The Festival is an oasis where people listen to other people. The paradox of poetry is that almost everybody writes poetry but almost nobody reads it … It is paradigmatic for modern society, where everybody wants to express himself and hear his own voice and almost nobody wants to listen to others … Monologues among the deafs …

Photo by: Roxland

24. Kazakhstan: Maria Vilkoviskaya

![]()

Nothing to be seen

Photo: The pit in which I stand in this photo was formerly Lake Sairan. Now there are plans to build an aquarium here.

Photo by: Ruslan Getmantchyuk

25. Latvia: Sergey Moreino

![]()

Sometimes it’s just the poetry / which holds together / the home and the today

Photo: In my photo, the big book on the left is Riga – Stately Lady In The Middle Of The Baltics. The small book on the right is The Poem About Bread by Imants Ziedonis, icon of Latvian poetry, who died in February, 2013 in both the original and the Russian translation by Lyudmila Azarova, another literary icon from Latvia. She died in 2012.

Photo by: Franziska Zwerg

26. Liechtenstein: Hansjörg Quaderer

![]()

Art=Oxygen

Photo: We took this photo in front of the Town Hall in my hometown of Schaan, Liechtenstein.

Photo by: Irmgard Schreiber

27. Lithuania: Laurynas Katkus

![]()

Blind words / show the way

Photo: This photo was taken on a street in Vilnius.

28. Luxembourg: Luc Spada

![]()

Do we really need it?

Photo: This photo was taken in front of three stop signs (a symbolic aspect of prohibition), in front of a poster announcing a circus event (as a metaphor for the literary field and as an event beyond poetry) and in front of a church tower (as a metaphor for church politics).

Photo by: Claude D. Conter

29. Malta: Keith Borg

![]()

Poetry is the soul divided whose driblets soothe the cracks in the Maltese heart

Photo: This photo was taken on top of the roof of my mother’s house overlooking St. Helen’s Church in my hometown of Birkirkara. It is where I grew up and became who I am today.

Photo by: Michelle Bonnici

30. Macedonia: Nikola Madzirov

![]()

Silence between the walls. Poet between the silences.

Photo: The house in this photo is the abandoned and nearly-de- stroyed home of my childhood, in which I hid my books and comics from my parents. Books were forbidden for me to read. That was part of my verbal and silent opening to the world.

Photo by: Andon Davchev

31. Moldavia: Alexandru Vakulovski

![]()

How nicely the Parliament burnt. April, 7th, 2009

Photo: This photo was taken in front of the Moldavian Parliament in Chişinău. Although the Parliament building and President’s office were burned during the protests of April 7, 2009, no one knows who did it. No one has been punished for the murders, tortures and rapes that took place after the protests. Moldova has been without a president for three years. The President’s office and Parliament buildings are currently closed.

Photo by: Moni Stãnilã

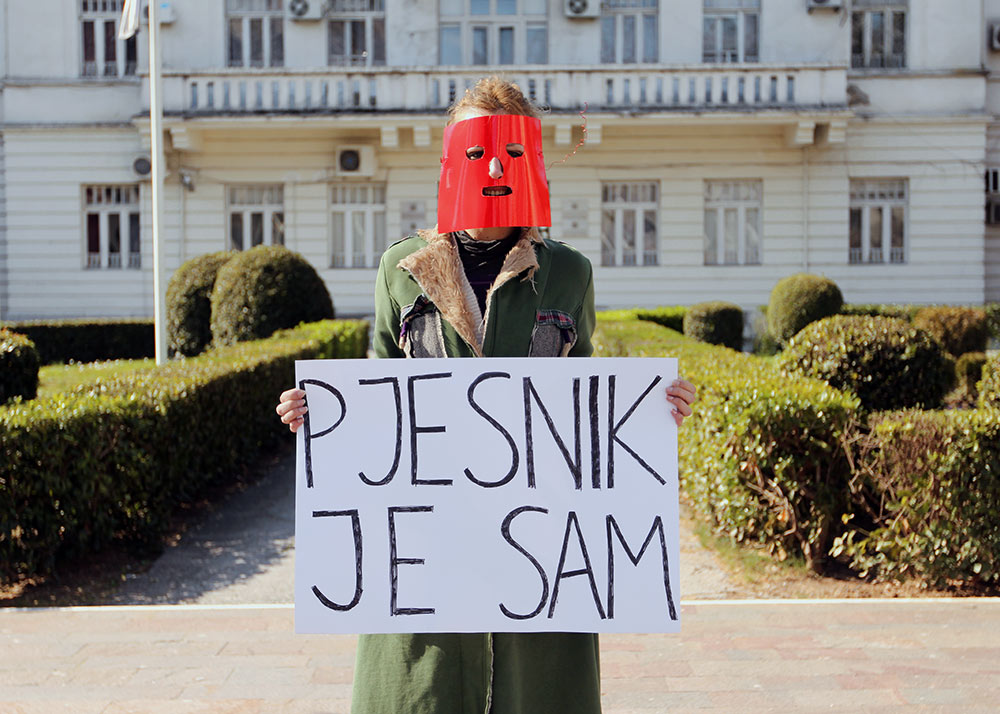

32. Montenegro: Tanja Bakić

![]()

The poet is on their own

Photo: In the background of this photo is the Town Hall of Podgorica.

Photo by: Marina Knezevic

Poets / Your anthropometric passports

Photo: The photo was taken in Marseille, where I live, in close proximity of the port, in a very open and simultaneously very closed and heavily-proctected place: Esplanade du J4.

Photo by: Sarah Wiechers

17. Georgia: Paata Shamugia

Poetry gets you stoned

Photo: This photo of me, surrounded with the busts of famous Georgian authors, was taken in the yard of the Museum of Literature.

Photo by: Nino Gogua

18. Germany: Sabine Scho

To tap the planet

Photo: This photo was taken on Teufelsberg, a mountain of rubble in Berlin, in front of the ruins of an American communications interception station, which were part of the global spy network Echelon during the Cold War.

Photo by: Matthias Holtmann

19. Greece: Yannis Stiggas

To sharpen freedom inside us

Photo: The mask is like a cage. It reminds me of The Man in the Iron Mask and is strongly related to the verse on the cardboard. This photo was taken in my apartment. It has only one window, the only source of light. All the other corners are quite dark.

Photo by: Eleni Chrysopoulou

20. Hungary: Petra Szőcs

To stop you forgetting

Photo: I once lived nearby for a winter.

Photo by: Nagy Botond

21. Ireland: Máighréad Medbh

Law rules / Poetry appeals

Photo by: Ayoma Bowe & David Maybury, Poetry Ireland

22. Iceland: Kristín Ómarsdóttir

Butter, buns, powder / polar bears and poets, endangered?

Photo: This photo was taken in the downtown area of Reykjavík, the main shopping artery of the city. In the background are hotels and a fast food restaurant. On the right is a model of a polar bear and its cub, shackled together to a souvenir shop.

Photo by: Davíd Kjartan Gestsson

23. Italy: Claudio Pozzani

Write one poem less, read one poem more

Photo: The location of this photo is the Palazzo Ducale, the most important historical building in Genua, where I have been organizing the Genua International Poetry Festival since 1995. The Festival is an oasis where people listen to other people. The paradox of poetry is that almost everybody writes poetry but almost nobody reads it … It is paradigmatic for modern society, where everybody wants to express himself and hear his own voice and almost nobody wants to listen to others … Monologues among the deafs …

Photo by: Roxland

24. Kazakhstan: Maria Vilkoviskaya

Nothing to be seen

Photo: The pit in which I stand in this photo was formerly Lake Sairan. Now there are plans to build an aquarium here.

Photo by: Ruslan Getmantchyuk

25. Latvia: Sergey Moreino

Sometimes it’s just the poetry / which holds together / the home and the today

Photo: In my photo, the big book on the left is Riga – Stately Lady In The Middle Of The Baltics. The small book on the right is The Poem About Bread by Imants Ziedonis, icon of Latvian poetry, who died in February, 2013 in both the original and the Russian translation by Lyudmila Azarova, another literary icon from Latvia. She died in 2012.

Photo by: Franziska Zwerg

26. Liechtenstein: Hansjörg Quaderer

Art=Oxygen

Photo: We took this photo in front of the Town Hall in my hometown of Schaan, Liechtenstein.

Photo by: Irmgard Schreiber

27. Lithuania: Laurynas Katkus

Blind words / show the way

Photo: This photo was taken on a street in Vilnius.

28. Luxembourg: Luc Spada

Do we really need it?

Photo: This photo was taken in front of three stop signs (a symbolic aspect of prohibition), in front of a poster announcing a circus event (as a metaphor for the literary field and as an event beyond poetry) and in front of a church tower (as a metaphor for church politics).

Photo by: Claude D. Conter

29. Malta: Keith Borg

Poetry is the soul divided whose driblets soothe the cracks in the Maltese heart

Photo: This photo was taken on top of the roof of my mother’s house overlooking St. Helen’s Church in my hometown of Birkirkara. It is where I grew up and became who I am today.

Photo by: Michelle Bonnici

30. Macedonia: Nikola Madzirov

Silence between the walls. Poet between the silences.

Photo: The house in this photo is the abandoned and nearly-de- stroyed home of my childhood, in which I hid my books and comics from my parents. Books were forbidden for me to read. That was part of my verbal and silent opening to the world.

Photo by: Andon Davchev

31. Moldavia: Alexandru Vakulovski

How nicely the Parliament burnt. April, 7th, 2009

Photo: This photo was taken in front of the Moldavian Parliament in Chişinău. Although the Parliament building and President’s office were burned during the protests of April 7, 2009, no one knows who did it. No one has been punished for the murders, tortures and rapes that took place after the protests. Moldova has been without a president for three years. The President’s office and Parliament buildings are currently closed.

Photo by: Moni Stãnilã

32. Montenegro: Tanja Bakić

The poet is on their own

Photo: In the background of this photo is the Town Hall of Podgorica.

Photo by: Marina Knezevic

33. Netherlands: Tsead Bruinja

![]()

ON YOUR BACK / The land is the sky within us / nothing will change that, no farm or apartment building / look for a high hill you’ve already got a back

Photo: The background of the photo is the sky above Amsterdam and the flag is Frisian. My slogan is basically about how we should all look at the sky a bit more and that our governments, etc. are quite transitory, just like us. I would lay down in the meadow in front of our house and just look at the sky. Unfortunately the grass is not that tall on our roof. Once when I was very young I was staring at the clouds from my bedroom window and fell one floor down. I didn’t break anything but maybe my head was shook up a bit. My future career as a rocket scientist changed into a future career as a scientist of poetry.

Photo by: Saskia Stehouwer

34. Norway: Cornelius Jakhelln

![]()

Poetry shall hover / out of the State in Time / towards the forgotten land

Photo: I took this photo in Ljubljana, Slovenia, in front of a building that looks very much like the post-war architecture you find in Oslo. As a citizen both of Norway and of the NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst) State in Time, Laibach is the other capital of my two nationalities. The poetic slogan touches on this dual citizen- ship, an idea in itself that can be regarded as fictitious. I am a poet who belongs both to a geographical and a temporary state.

Photo by: Sturmgeist

35. Poland: Patryk Zimny

![]()

We don’t know places, we don’t know history; / all we know is the literature of each epoch

Photo: The theme is »Traces of Weiser«. In the background are the surroundings of the Weiser bridge, which is due to be knocked down soon … Which corresponds to the slogan, just as the slogan corresponds to the bridge and its near future.. Making something eternal …

Photo by: Joanna Pruszyńska

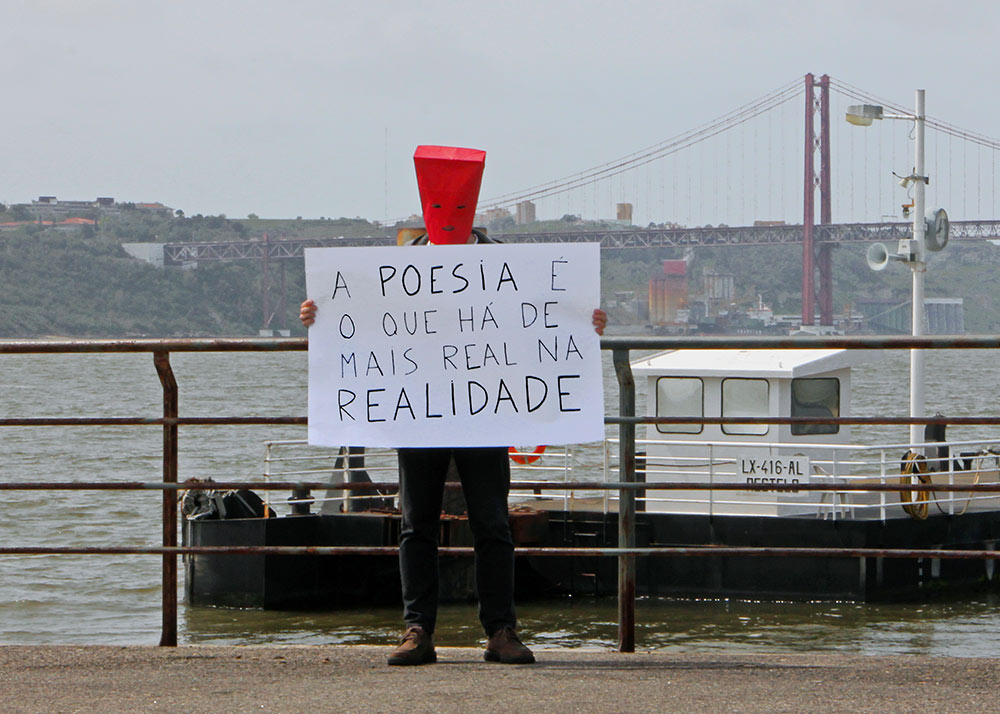

36. Portugal: José Mário Silva

![]()

There is nothing more real in reality than poetry

Photo: Taken in Cais do Sodré in Lisbon.

Photo by: Gonçalo Riscado

37. Romania: Svetlana Cârstean

![]()

Your future is here, / it will be heroic, I promise you, / and so it was

Photo: This photo was taken in the center of Bucharest, in a place named Piata Verona, which is very close to my old place on Xenopol street. For me, this is the most beautiful neighbourhood in Bucharest. Old and beautiful streets and houses. In front of me is the Anglican Church, behind me a big garden. But when you look at this photo, you’d never know what is around me. You can see a lot of green, but as if in a prison, beyond the fence. Nor would you ever know which side of the fence I’m on. Am I in the prison, or are you? This is what my life is like in Bucharest, in Romania.

Photo by: Tudor Paul-Badescu

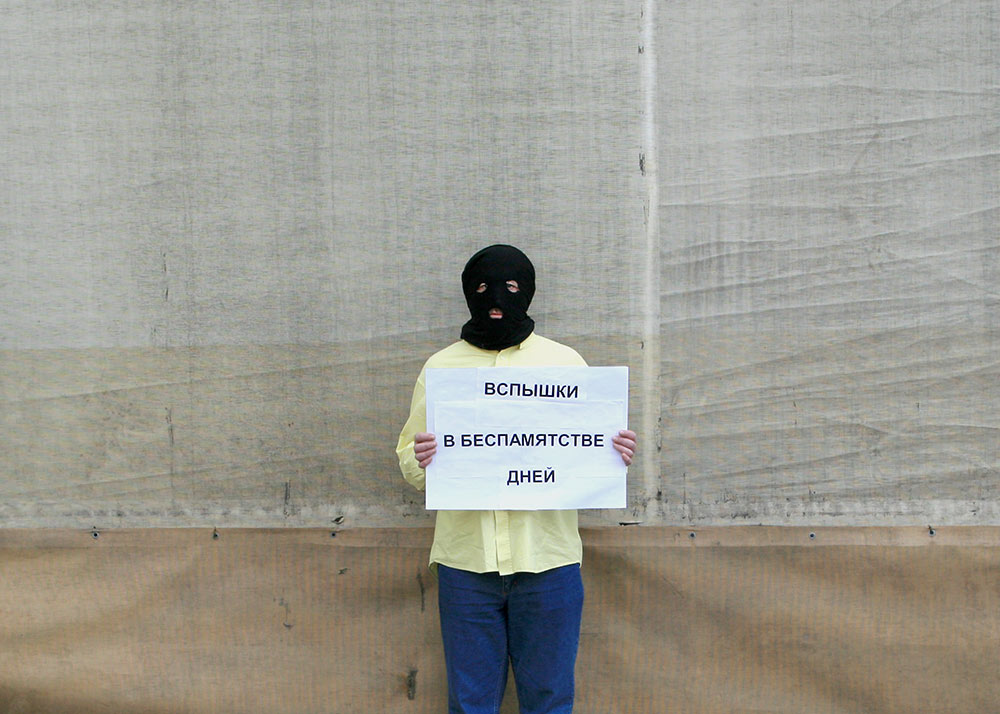

38. Russia: Stanislav Lvovsky

![]()

Flashes from oblivion

Photo: A poem is a kind of remembrance. This photo was taken by the soon-to-be demolished Supreme Court Military Collegium building in Moscow where tens of thousans were executed in 1937–1938.

39. Sweden: Leif Holmstrand

![]()

Some home languages are too big / for the home to swallow

Photo: This photo was taken in the poet’s house in a back room.

Photo by: Per Bergström

40. Switzerland: Michael Fehr

![]()

The price you pay / for living with a large mass and high luminosity / is ultimately the explosion

Photo: This photo was taken in the Kornhaus in Bern. Models: Maria Sigrist (left), Ernestyna Orlowska (right).

Photo by: Patrick Savolainen

41. Serbia: Dragana Mladenović

![]()

Poetry is bread

Photo: I stand on the top of the canon (gun) that was used as the fireworks to notify residents of Pancevo about the arrivals of steamships in local port. It was used in the second half of the 19th century. The canon is buried in front of the former City Hall (Magistrate), nowadays the National Museum of Pancevo.

Photo by: Bogdan Petrov

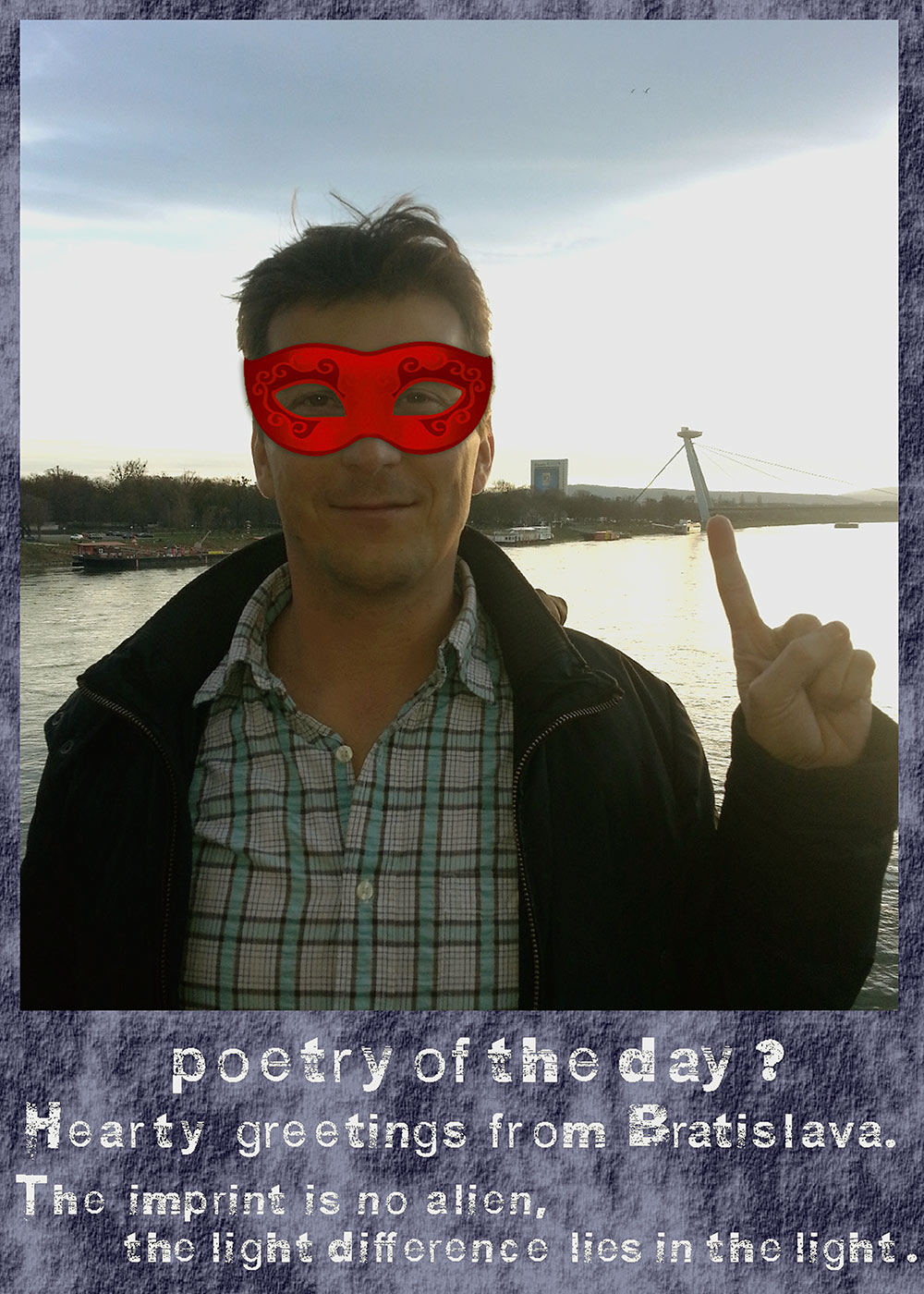

42. Slovakia: Martin Solotruk

![]()

Poetry of the day? / Hearty greetings from Bratislava. / The imprint is no alien, / the light difference lies in the light.

Photo by: Martin Solotruk

43. Slovenia: Aleš Šteger

![]()

Everyone is / eats a song

Photo: This photo was taken in Ljubljana, in front of the Govern- ment House and the Cankarjev Dom, the largest cultural center in Slovenia. The statue is of the Communist politician and ideologist Boris Kidrič.

Photo by: Marko Hercog

44. Spain: Martí Sales

![]()

Poetry is useless / (that’s why we like it)

Photo: In the background of this photo you can see the Roman- esque church of Sant Pau del Camp, one of the oldest churches in Barcelona. The small building is located in the middle of Raval district, a lively, multicultural and creative neighbourhood, where Martí Sales lives.

Photo by: Eduard Escoffet

45. Turkey: Ömer Erdem

![]()

The City: human beings’ new tomb / while the poem was burying itself there secretly it / got caught on a patriotic surveillance camera

Photo: The place where the photo was taken is the graveyard within the Galata Lodge of Mevlevi Dervish’s. The graveyard is called The »Place of the Silents« meaning where the Silent Ones reside. Mevlevi’s are the followers of the 13th century poet Mewlānā Jalāl ad-Dīn Rumi and the »Place of the Silents« is the resting place of those who have found their existence within the great flux. This is the place of existence and nothingness, just like poetry is presence and absence at the same time. And poetry in today’s world is present but invisible, absent.

Photo by: Fatma Cihan Akkartal

46. UK: Sabrina Mahfouz

![]()

Sometimes, the low / light of the London sky / reminds me of another LIFE … / And so I write.

Photo: Taken on the banks of the River Thames, in the background Big Ben at al.

Photo by: Ben Larpent

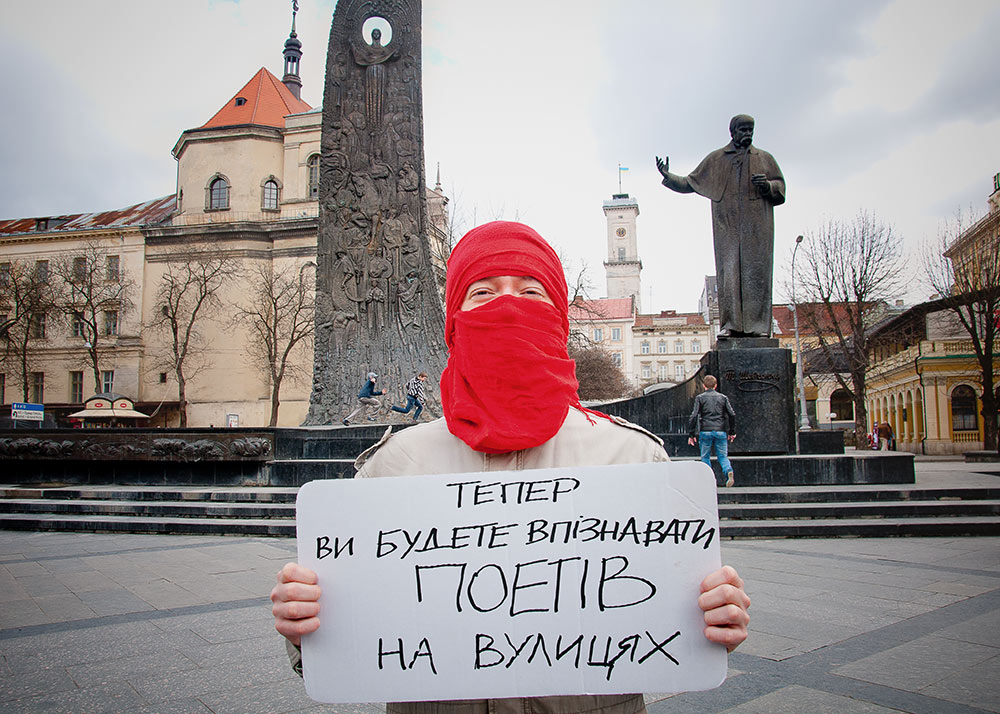

47. Ukraine: Ostap Slyvynsky

![]()

Now you will recognize the poets on the street

Photo: Square near Shevchenko’s monument in Lviv. A popular meeting point, but the Poet himself (Taras Shevchenko) remains almost unnoticed and unrecognized. It perfectly corresponds with the slogan.

Photo by: Yurij Dvornyk

ON YOUR BACK / The land is the sky within us / nothing will change that, no farm or apartment building / look for a high hill you’ve already got a back

Photo: The background of the photo is the sky above Amsterdam and the flag is Frisian. My slogan is basically about how we should all look at the sky a bit more and that our governments, etc. are quite transitory, just like us. I would lay down in the meadow in front of our house and just look at the sky. Unfortunately the grass is not that tall on our roof. Once when I was very young I was staring at the clouds from my bedroom window and fell one floor down. I didn’t break anything but maybe my head was shook up a bit. My future career as a rocket scientist changed into a future career as a scientist of poetry.

Photo by: Saskia Stehouwer

34. Norway: Cornelius Jakhelln

Poetry shall hover / out of the State in Time / towards the forgotten land

Photo: I took this photo in Ljubljana, Slovenia, in front of a building that looks very much like the post-war architecture you find in Oslo. As a citizen both of Norway and of the NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst) State in Time, Laibach is the other capital of my two nationalities. The poetic slogan touches on this dual citizen- ship, an idea in itself that can be regarded as fictitious. I am a poet who belongs both to a geographical and a temporary state.

Photo by: Sturmgeist

35. Poland: Patryk Zimny

We don’t know places, we don’t know history; / all we know is the literature of each epoch

Photo: The theme is »Traces of Weiser«. In the background are the surroundings of the Weiser bridge, which is due to be knocked down soon … Which corresponds to the slogan, just as the slogan corresponds to the bridge and its near future.. Making something eternal …

Photo by: Joanna Pruszyńska

36. Portugal: José Mário Silva

There is nothing more real in reality than poetry

Photo: Taken in Cais do Sodré in Lisbon.

Photo by: Gonçalo Riscado

37. Romania: Svetlana Cârstean

Your future is here, / it will be heroic, I promise you, / and so it was

Photo: This photo was taken in the center of Bucharest, in a place named Piata Verona, which is very close to my old place on Xenopol street. For me, this is the most beautiful neighbourhood in Bucharest. Old and beautiful streets and houses. In front of me is the Anglican Church, behind me a big garden. But when you look at this photo, you’d never know what is around me. You can see a lot of green, but as if in a prison, beyond the fence. Nor would you ever know which side of the fence I’m on. Am I in the prison, or are you? This is what my life is like in Bucharest, in Romania.

Photo by: Tudor Paul-Badescu

38. Russia: Stanislav Lvovsky

Flashes from oblivion

Photo: A poem is a kind of remembrance. This photo was taken by the soon-to-be demolished Supreme Court Military Collegium building in Moscow where tens of thousans were executed in 1937–1938.

39. Sweden: Leif Holmstrand

Some home languages are too big / for the home to swallow

Photo: This photo was taken in the poet’s house in a back room.

Photo by: Per Bergström

40. Switzerland: Michael Fehr

The price you pay / for living with a large mass and high luminosity / is ultimately the explosion

Photo: This photo was taken in the Kornhaus in Bern. Models: Maria Sigrist (left), Ernestyna Orlowska (right).

Photo by: Patrick Savolainen

41. Serbia: Dragana Mladenović

Poetry is bread

Photo: I stand on the top of the canon (gun) that was used as the fireworks to notify residents of Pancevo about the arrivals of steamships in local port. It was used in the second half of the 19th century. The canon is buried in front of the former City Hall (Magistrate), nowadays the National Museum of Pancevo.

Photo by: Bogdan Petrov

42. Slovakia: Martin Solotruk

Poetry of the day? / Hearty greetings from Bratislava. / The imprint is no alien, / the light difference lies in the light.

Photo by: Martin Solotruk

43. Slovenia: Aleš Šteger

Everyone is / eats a song

Photo: This photo was taken in Ljubljana, in front of the Govern- ment House and the Cankarjev Dom, the largest cultural center in Slovenia. The statue is of the Communist politician and ideologist Boris Kidrič.

Photo by: Marko Hercog

44. Spain: Martí Sales

Poetry is useless / (that’s why we like it)

Photo: In the background of this photo you can see the Roman- esque church of Sant Pau del Camp, one of the oldest churches in Barcelona. The small building is located in the middle of Raval district, a lively, multicultural and creative neighbourhood, where Martí Sales lives.

Photo by: Eduard Escoffet

45. Turkey: Ömer Erdem

The City: human beings’ new tomb / while the poem was burying itself there secretly it / got caught on a patriotic surveillance camera

Photo: The place where the photo was taken is the graveyard within the Galata Lodge of Mevlevi Dervish’s. The graveyard is called The »Place of the Silents« meaning where the Silent Ones reside. Mevlevi’s are the followers of the 13th century poet Mewlānā Jalāl ad-Dīn Rumi and the »Place of the Silents« is the resting place of those who have found their existence within the great flux. This is the place of existence and nothingness, just like poetry is presence and absence at the same time. And poetry in today’s world is present but invisible, absent.

Photo by: Fatma Cihan Akkartal

46. UK: Sabrina Mahfouz

Sometimes, the low / light of the London sky / reminds me of another LIFE … / And so I write.

Photo: Taken on the banks of the River Thames, in the background Big Ben at al.

Photo by: Ben Larpent

47. Ukraine: Ostap Slyvynsky

Now you will recognize the poets on the street

Photo: Square near Shevchenko’s monument in Lviv. A popular meeting point, but the Poet himself (Taras Shevchenko) remains almost unnoticed and unrecognized. It perfectly corresponds with the slogan.

Photo by: Yurij Dvornyk

Texts about the project:

What’s the Point of Poetry?

Poets, as well as anyone else who has an interest in poetry, are repeatedly confronted with this question, and it leads to a strange need for explanation. Finding a response has weighed on my mind for quite some time. The question itself draws its seeming authority from the observation that poetry has no market value and its reception requires an understanding that would de-celerate our perception of time and is therefore diametrically opposed to it. To access a poem, one must engage. That is so.

Poetry is humanity’s oldest art form and developed as a meaning-giving element between music and dance. In spite of all media revolutions, this relationship continues to exist today. Or rather: poetry is now receiving growing attention. The poem is the art form of language and is made up of sound, rhythm, and what the chosen words and articulations want to mean. Thus, the poem is recognized all over the world and in every language: it is a unique, aesthetically formed use of language that sets itself apart from that used in everyday life.

In the fall of 2012, I discovered the work of the Minsk-based artist Sergey Shabohin at an art fair in Georgia. His conceptual art provokes debate – it inspired me. Shabohin developed a photo-aesthetic framework for the question What’s the point of poetry? This frame- work places the given content parameters – poetry, society, and homeland – in relation to each other: all of the poets demonstrate under a mask and hold a banner or sign with their responses in a place that signifies home to them – in earnest or with counteractive implications. In this way, the mausoleum of Enver Hoxha in Albania, the once inflamed parliament in Moldova, or the former U. S. spy station in Eastern Europe come back into the picture, but now with a new connotation.

The question What’s the point of poetry? is also ironically directed at the notion that poems are made to be functional and used in a utilitarian manner. The 47 poets from 47 countries that are members or candidates of the Council of Europe have answered this question with a slogan for themselves, for their countries, and for us. As intended with the staging of the photos, they become allies in their individual agendas – from Iceland to Kasakhstan or from Norway to Malta. The poets were chosen by our partner institutions in all of the countries.

Poetry is humanity’s oldest art form and developed as a meaning-giving element between music and dance. In spite of all media revolutions, this relationship continues to exist today. Or rather: poetry is now receiving growing attention. The poem is the art form of language and is made up of sound, rhythm, and what the chosen words and articulations want to mean. Thus, the poem is recognized all over the world and in every language: it is a unique, aesthetically formed use of language that sets itself apart from that used in everyday life.

In the fall of 2012, I discovered the work of the Minsk-based artist Sergey Shabohin at an art fair in Georgia. His conceptual art provokes debate – it inspired me. Shabohin developed a photo-aesthetic framework for the question What’s the point of poetry? This frame- work places the given content parameters – poetry, society, and homeland – in relation to each other: all of the poets demonstrate under a mask and hold a banner or sign with their responses in a place that signifies home to them – in earnest or with counteractive implications. In this way, the mausoleum of Enver Hoxha in Albania, the once inflamed parliament in Moldova, or the former U. S. spy station in Eastern Europe come back into the picture, but now with a new connotation.

The question What’s the point of poetry? is also ironically directed at the notion that poems are made to be functional and used in a utilitarian manner. The 47 poets from 47 countries that are members or candidates of the Council of Europe have answered this question with a slogan for themselves, for their countries, and for us. As intended with the staging of the photos, they become allies in their individual agendas – from Iceland to Kasakhstan or from Norway to Malta. The poets were chosen by our partner institutions in all of the countries.

It becomes clear from the poets’ points of view that the poem rejects any direct claim and nevertheless remains responsible for all areas of human and social life. One can observe that the poetological self-perception of poetry is varied, just like the distinction between Eastern and Western Europe can still be identified as the limes.

Poems are, as this exhibition explains, small power plants with a great impact on us humans. They belong to us, though we can’t quite explain their effect. They are also beautiful when they are disturbingly unwieldy and resist the ideological linguistic garbage and all of the media noise surrounding us, even when they avoid all of that.

The German poet Sabine Scho answers the question What’s the point of poetry?: »To tap the planet«; Marti Sales from Spain: »Poetry is useless (that’s why we like it)«; the Greek poet Yannis Stiggas offers the response: »To sharpe freedom inside us«; and the poet from Sweden, Leif Holmstrand, sums up: »Some home languages are too big for the home to swallow«.

What’s the Point of Poetry? would like to initiate a Europe-wide discussion on the self-perception of this art and its artists in social realities. The exhibition is structured so that it can be brought to other countries at the lowest possible cost after its premiere in Berlin.

I would like to thank all of the participating poets, photographers, partner institutions, the slogan translators, the artist Sergey Shabohin, and especially Alexander Filyuta, who was responsible for overseeing the project.

With equal importance, thanks go out to those who made the exhibition financially possible, the Hauptstadtkulturfonds, the Akademie der Künste, The British Council, The Mandala Hotel and many private contributors.

Poems are, as this exhibition explains, small power plants with a great impact on us humans. They belong to us, though we can’t quite explain their effect. They are also beautiful when they are disturbingly unwieldy and resist the ideological linguistic garbage and all of the media noise surrounding us, even when they avoid all of that.

The German poet Sabine Scho answers the question What’s the point of poetry?: »To tap the planet«; Marti Sales from Spain: »Poetry is useless (that’s why we like it)«; the Greek poet Yannis Stiggas offers the response: »To sharpe freedom inside us«; and the poet from Sweden, Leif Holmstrand, sums up: »Some home languages are too big for the home to swallow«.

What’s the Point of Poetry? would like to initiate a Europe-wide discussion on the self-perception of this art and its artists in social realities. The exhibition is structured so that it can be brought to other countries at the lowest possible cost after its premiere in Berlin.

I would like to thank all of the participating poets, photographers, partner institutions, the slogan translators, the artist Sergey Shabohin, and especially Alexander Filyuta, who was responsible for overseeing the project.

With equal importance, thanks go out to those who made the exhibition financially possible, the Hauptstadtkulturfonds, the Akademie der Künste, The British Council, The Mandala Hotel and many private contributors.

Thomas Wohlfahrt

Director of Literaturwerkstatt Berlin

Head of the Berlin Poetry Festival

Director of Literaturwerkstatt Berlin

Head of the Berlin Poetry Festival

What’s the Point of Poetry Today?

The story of this project began in Minsk in 2010, where the artist Sergey Shabohin recorded a video in which the protagonists of the Belarusian contemporary art scene – their faces hidden behind masks – presented various slogans. According to Sergey Shabohin, the art-terrorist gesture symbolized the state of affairs for artists in modern societies. It is very difficult for an artist to gain public attention, no matter what subject he wants to address. Shortly thereafter, the project spread internationally. The Belarusian artists began to travel the world and photograph themselves in public spaces with slogans in their hands and masks over their heads.

The slogans made reference to the problems of contemporary art in each country. The exhibition What’s the Point of Poetry? features poets wearing the mask. The task was to bring together terms like ›poetry‹, ›society‹, and ›homeland‹ with a slogan. The poets not only represent themselves, but act as the voice of their respective countries. For the implementation of the art-activist gesture, the poet had to find a public space and follow clear guidelines that were given for the production of the photo.

Now how do these guidelines have an influence on the poetic slogan? Do the poets defy at least a few aspects of it, for example, disregarding the question of the relationship between poetry and homeland? Or, through their expression, do they turn it into something completely new – ironic, dramatic, or serious – because they go out into a public space and have to present their slogans in public? Does the slogan make sense, is it motivating, or is it at least exciting?

These questions will inevitably lead to more questions. Do the poets manage to represent their countries without fear and explore the boundary between the individual (freedom of poetic expression) and the general public (justice), as well as find a way to define that boundary today? What about this boundary in regards to poetry, their individual countries, and the joint European space? What do we think today about the boundaries in general – spatial, temporal, social, cultural, sexual – and how can they be overcome?

The answers to these questions depend on the extent that poetry is linked, on the one hand with the concept of homeland and, on the other, the concept of society. It also depends on how the language, for which the poet is considered a means of subsistence (Brodsky), is still seen today as »the house of being« (Heidegger). Who lives in this house and in what way; who or what stands outside of its borders?

In many Central and Eastern European countries, these questions arose with intensity after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Suddenly, a conversation about collective identity and origin set itself in motion again. Simultaneously, terms like ›nation‹ and ›homeland‹ were charged with new meaning. Meanwhile, what happened to the old meaning? To national pride, modern national culture, or the romantic ideas of harmony and genius?

The slogans made reference to the problems of contemporary art in each country. The exhibition What’s the Point of Poetry? features poets wearing the mask. The task was to bring together terms like ›poetry‹, ›society‹, and ›homeland‹ with a slogan. The poets not only represent themselves, but act as the voice of their respective countries. For the implementation of the art-activist gesture, the poet had to find a public space and follow clear guidelines that were given for the production of the photo.

Now how do these guidelines have an influence on the poetic slogan? Do the poets defy at least a few aspects of it, for example, disregarding the question of the relationship between poetry and homeland? Or, through their expression, do they turn it into something completely new – ironic, dramatic, or serious – because they go out into a public space and have to present their slogans in public? Does the slogan make sense, is it motivating, or is it at least exciting?

These questions will inevitably lead to more questions. Do the poets manage to represent their countries without fear and explore the boundary between the individual (freedom of poetic expression) and the general public (justice), as well as find a way to define that boundary today? What about this boundary in regards to poetry, their individual countries, and the joint European space? What do we think today about the boundaries in general – spatial, temporal, social, cultural, sexual – and how can they be overcome?

The answers to these questions depend on the extent that poetry is linked, on the one hand with the concept of homeland and, on the other, the concept of society. It also depends on how the language, for which the poet is considered a means of subsistence (Brodsky), is still seen today as »the house of being« (Heidegger). Who lives in this house and in what way; who or what stands outside of its borders?

In many Central and Eastern European countries, these questions arose with intensity after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Suddenly, a conversation about collective identity and origin set itself in motion again. Simultaneously, terms like ›nation‹ and ›homeland‹ were charged with new meaning. Meanwhile, what happened to the old meaning? To national pride, modern national culture, or the romantic ideas of harmony and genius?

It seems that these questions concern contemporary artists. Does poetry also have the ability to respond to them and provide answers? If modern and especially actionist art is interactive (and it is, because otherwise it would be dead), then what can be said about the poetry? Is the poet capable of going beyond the solutions inherent in art toward that general space of the senses and life that combines with our responsibility to ourselves and to others?

And how would this space look today?

This last question allows us to emphasize another dimension of the connection or the disparity between poetry, homeland, and society. This is the dimension of present day Europe. What can the modern poet assert about Europe? And what type of image of Europe is revealed in the array of poetic slogans? Is it an image of Europe’s past, present, or future? Does it describe a European poly- or cacophony?

A slogan presented in a public space can only be effective today if it makes a statement about something really meaningful. The mask anonymizes, it makes the wearer clandestine and thus unpredictable and even threatening. Maybe this aspect in particular creates a way to recognize »the violence and hatred of things« from behind the mask of language, which, according to Deleuze, gain the upper hand if »other things in the structure of the world« are missing. Isn’t this what occurs as the definitive metaphor of our coexistence? Nationality, language, sex, color, age, or wealth remain largely invisible in a world that is dominated by generalization and whose flipside is isolation.

Can words help here, poetic words? Are they able to connect while maintaining heterogeneity, and can they unify without ignoring the differences (Foucault)? Can poetry both resist the violence of things if I am separated from the other (Deleuze), as well as the violence of the language itself, which moves the things into a dimension of meanings that is strange to them (Žižek)? Can the figure of the »poet in the public space with an actionist mask and with a slogan in his hand« resist the violence of things without falling back on the violence of words, so that it remains possible for him to assert freedom, whose flipside is not only more freedom, but also justice?

This last question allows us to emphasize another dimension of the connection or the disparity between poetry, homeland, and society. This is the dimension of present day Europe. What can the modern poet assert about Europe? And what type of image of Europe is revealed in the array of poetic slogans? Is it an image of Europe’s past, present, or future? Does it describe a European poly- or cacophony?

A slogan presented in a public space can only be effective today if it makes a statement about something really meaningful. The mask anonymizes, it makes the wearer clandestine and thus unpredictable and even threatening. Maybe this aspect in particular creates a way to recognize »the violence and hatred of things« from behind the mask of language, which, according to Deleuze, gain the upper hand if »other things in the structure of the world« are missing. Isn’t this what occurs as the definitive metaphor of our coexistence? Nationality, language, sex, color, age, or wealth remain largely invisible in a world that is dominated by generalization and whose flipside is isolation.

Can words help here, poetic words? Are they able to connect while maintaining heterogeneity, and can they unify without ignoring the differences (Foucault)? Can poetry both resist the violence of things if I am separated from the other (Deleuze), as well as the violence of the language itself, which moves the things into a dimension of meanings that is strange to them (Žižek)? Can the figure of the »poet in the public space with an actionist mask and with a slogan in his hand« resist the violence of things without falling back on the violence of words, so that it remains possible for him to assert freedom, whose flipside is not only more freedom, but also justice?

Olga Shparaga

assisted by Sergey Shabohin

assisted by Sergey Shabohin