Article in English:

ID: P12.8

Title:

Regeneration in Partisan Conditions

Date:

2011

Resource:

Moscow Art Magazine, issue 83, Moscow, Russia

Autor:

Sergey Shabohin

Intro:

An overview of the situation in Belarusian art of the 2000s written for the Moscow Art Magazine “The zeroes: How was it?”

The fact that the Moscow Art Magazine charged young artists from Belarus, Russia and Ukraine with writing about the main trends in the art of the 2000s is rather symptomatic. We are the generation of perestroika, whose professional career have began in the second half of the zeroes, the hostages of aesthetic rebellion, the bearers of post-Soviet complexes and a new attitude towards art. Despite our conditional similarity, three separated allied states represented by us have evolved differently, without looking back at each other. If you try to imagine a comic strip, which depicts the era of 2000s in each of our three countries, the Belarusian variant would look too unpretentious in comparison with the orange pages of Ukrainian variant. For decades, the Belarusian authorities haven’t changed and, since 1994, have gradually become a pseudo-socialist monarchy. I am sure that the Ukrainians and the Russians, who may not have a clue about what is happening in neighboring Belarus, will imagine Belarusian comic strip like a sad painting book (although, speaking frankly, even the Belarusians often imagine it in the same way).

Peter Verzilov, a member of the art group “War”, inviting Belarusian artists to exhibit their works on the forum of civil activists “The Last Autumn”, explained his choice by the following phrase: “The modern situation in Belarus is a successful illustration, a scarecrow, demonstrating to the Russian authorities where Russia may be”. This is a typical example of how people see Belarus – “the last bastion of dictatorship in Europe” – and sometimes it seems that this simplistic image is beneficial for everyone: for Russian authorities as a comparative example, for European countries as something exotic, and for leaders of Belarusian culture as a reason for confrontation. Over the past few years, whether because of the Belarusians’ increased activity, or ‘cause of the general politicization of art and coming the fashion for authoritarian regimes and anti-authoritarian revolutions, neighboring countries have tried to explore the situation in contemporary Belarusian art. Most of the initiatives come from Poland, Sweden, Germany and Lithuania. In Russia and Ukraine Belarusian art is rare and appears almost only in commerce or through museum fine art exchange. The organizers of numerous exhibitions, biennales and festivals in Russia and Ukraine do not invite the Belarusians to participate, and, of course, it is connected not with the absence of Belarusian product, but with the lack of interest to this product from the neighbors (perhaps, partly because Belarus’ cultural isolation and its “exotic” resemble the Russian and Ukrainian models too much). To be fair it should be noted that there is no Ukrainian or Russian art in Belarus either. But we have another problem – here even Belarusian art is represented quite poorly.

Peter Verzilov, a member of the art group “War”, inviting Belarusian artists to exhibit their works on the forum of civil activists “The Last Autumn”, explained his choice by the following phrase: “The modern situation in Belarus is a successful illustration, a scarecrow, demonstrating to the Russian authorities where Russia may be”. This is a typical example of how people see Belarus – “the last bastion of dictatorship in Europe” – and sometimes it seems that this simplistic image is beneficial for everyone: for Russian authorities as a comparative example, for European countries as something exotic, and for leaders of Belarusian culture as a reason for confrontation. Over the past few years, whether because of the Belarusians’ increased activity, or ‘cause of the general politicization of art and coming the fashion for authoritarian regimes and anti-authoritarian revolutions, neighboring countries have tried to explore the situation in contemporary Belarusian art. Most of the initiatives come from Poland, Sweden, Germany and Lithuania. In Russia and Ukraine Belarusian art is rare and appears almost only in commerce or through museum fine art exchange. The organizers of numerous exhibitions, biennales and festivals in Russia and Ukraine do not invite the Belarusians to participate, and, of course, it is connected not with the absence of Belarusian product, but with the lack of interest to this product from the neighbors (perhaps, partly because Belarus’ cultural isolation and its “exotic” resemble the Russian and Ukrainian models too much). To be fair it should be noted that there is no Ukrainian or Russian art in Belarus either. But we have another problem – here even Belarusian art is represented quite poorly.

There is nothing

While preparing this text, I was looking through the Moscow Art Magazine’s archives in searching of articles about Belarus. Finding only a few publications, I decided it would be appropriate to try to give an impartial, summarizing estimate of the 2000s, simultaneously highlighting the key processes in contemporary Belarusian art since the 1990s. For this reason, I interviewed several key members of the Belarusian art process of the 1990s– the late 2000s. The first reaction of almost everyone I’ve talked with was joyless stereotypic: “the zeroes were zeroes”, “there was nothing”, “everything was forbidden”. I also have heard such characteristics as “total depression”, “frozen swamp”, “cultural menopause”.

Aleksei Lunev:

“There is Nothing”,

from his series Black Market,

2009

“There is Nothing”,

from his series Black Market,

2009

The melancholy of contemporary Belarusian art appeared from the previous inspiration and the following shock suspension. In Belarus, it was a short period of liberalization in 1991–1995, which had began with the attainment of independence. Those days an unusual freedom was felt on the tide of perestroika: new galleries were opened, the Soros Foundation began its activities, a new generation of active teachers and students came, festivals of contemporary art were conducted (the most notable of which is “In-formation” on the “Salt stocks” in Vitebsk). This period of creative permissiveness people feel nostalgic about, perhaps, was too short, but exactly during this period the main progressive vector of modern art was made and a common understanding of modern Belarus has developed. A year after coming to power of Alexander Lukashenko the referendum was conducted, which had demonstrated that the new government is adjusted more resolutely than it seemed in the beginning. Soon the first wave of repression appeared, and working conditions for NGO deteriorated: unmanaged Soros Foundation was expelled from the country in 1997, and then galleries began to close one after another (the most important of which was The Sixth Line gallery). During the same period, the purge among students in art schools and universities was conducted. In a short period of time a huge number of cultural figures has left to the West, among them: Vadim Aladov, Alina Blumis, Maxim Vakulchik, Yegor Galuso, Zhanna Grak, Elena Davidovich, Evelyna Domnich, Andrei Dureiko, Boris Zaborov, Andrei Zadorin, Roman Zaslonov, Natalia Zaloznaya, Svetlana Zyabkina, Igor Kashkurevich, Alexander Knish, Alexander Komarov, Olga Kopenkina, Alexei Koshkarov, Andrei Loginov, Olga Maslovskaya, Dmitri Mahomet, Vika Mitrichenko, Alexander Rodin, Andrei Savitsky, Lena Sulkovskaia, Anna Sokolova, Alexei Terekhov, Igor Tishin, Roman Tratsyuk, Maxim Tyminko, Oleg Chornyi, Anna Shkolnikova, Gleb Shutov, Oleg Yushko, and others. The consequences of this emigration wave to Belarusian art are often defined as cultural genocide.

Andrei Dureiko:

The Academy of Arts,

1997

The Academy of Arts,

1997

Of course, people have left the country not only because of despair or aggressive political atmosphere. Many of them have used open borders to move to the West, but mostly they have left to get a qualification in European universities and art academies. There isn’t much choice of art schools in Belarus: most people have to enter the Belarusian Academy of Arts in Minsk. But even there the administration had pursued an authoritarian policy. The Rector Vasily Sharangovich put his hope in cultural nationalism, taking as an example the aesthetics of the Belarusian romantic literature of the first half – the middle of the XX century as a model of national cultural revival. The inspiration of Belarusian literature with its cult of spirituality, love of nature and rural aesthetics has created particularly favorable conditions for the development of graphic quality, decorativism and illustrativeness at the Academy. This strategy effectively assimilated classical academic traditions, affecting all the departments of the faculty of art. The transformation of the traditional “Repin” academism to a pseudo-academic graphic school with elements of decorative surrealism and lyrical expressionism determined the dominance of formalism and skill over the theory and understanding of art. Most of the representatives of the Belarusian Union of Artists work today in this typical manner. The Academy trains skilled journeymen, so the Directorate is always worried about dissidence among the students. And, of course, the administration of the Academy was scared by excessive activity of new students in the first half of the 1990s (they were trained by the young teachers, such as Igor Tishin and Natalya Zaloznaya, on the other, modernist examples). The students regularly carried out various actions and exhibitions the most famous of which was “Lessons of Bad Art” at the Palace of Arts. Its participants were the students expelled from the art school in those years. Right after the exhibition, the administration of the Academy quickly conducted the purge among students and about twenty people had to leave to study abroad.

Anti-individualistic policy is opposed to a cultural diversity: each year working conditions for NGO have become worse, which leads to the crisis of gallery business, impossibility of the origin of non-state cultural and educational institutions (universities, museums, etc.), shortage of specialized media and other private cultural initiatives. Obviously, an independent voice scares Belarusian officials – both from the Academy of Arts and the state apparatus. Another case in point is the story of the independent European Humanities University. Founded in 1992 in Minsk, the EHU was forced to close in 2004 and was able to resume its activities only in Lithuania (Vilnius) in autumn 2005.

The new millennium has begun in this depressive sterile atmosphere, which continued to dominate until the end of its first decade. Nevertheless, at the beginning of the 2000s several symbolic exhibitions of Belarusian artists were held: the last exhibition of the group “Nemiga-17” (at the State Tretyakov Gallery), “The Century Project” by Vladimir Tsesler and Sergei Voichenko, the exhibition of Sergei Kiryushchenko and Tamara Sokolova, artistic appropriation by Ruslan Vashkevich – though it is rather exceptions on the generally meager background.

In the zeroes all people have had to adjust to market conditions. Design, exhibitions for export, art as a commodity were the key trends in those years. Perhaps, during this period too many artists were retrained in designers and moved to Moscow, where they planned to get not only professional knowledge but also work in advertising, music and video taking, management, or fashion industry. It is possible that design “killed” more Belarusian artists than have left for the period of emigration, though, of course, some “victims” of design were able to overcome its effect by separating their art from their design activity.

Vladimir Tsesler:

Brooch,

2008

Brooch,

2008

The market forced artists to seek new strategies for survival, but galleries as a major source of sale were gone, therefore, during 2000s, many people have began to “produce” exhibition on imports. Works from overseas exhibitions were often sold all at once – not because of the exoticism of Belarusian art, but rather because of its decorativeness and cheapness. In Belarus, the collapse of socialist cultural model hasn’t led to the disintegration of the Soviet institutional pattern – centralized management (through the Ministry of Culture), the Union of Artists, and even the system of state orders have remained. But in reality market has succeeded in assimilating state cultural policy: workshops offered by the Union of Artists at a discounted price become more expensive each year, state orders are almost completely replaced by private orders, free exhibition at the Palace of Arts can be made only on an anniversary, and museums have learned to supplement their collection for humiliating payment. Therefore, for many artists the tactics of “art on import” gave hope for their professional existence.

The Academy of Art continues to produce annually professional decorators: designers (today the faculty of design has become more popular), graphic artists, monument sculptors, sculptors and decorators. It seems that it should be a high level of aesthetic culture in the country with such a big number of apprentices. Perhaps this is true in some part. We succeeded in decorating – fake and neat aesthetics is typical for Belarus. Belarusian towns, full of pseudo-socialistic window dressing and lifeless fictive restoration buildings, are deprived of deep historical strata. Even if the sterility of the palimpsest design company has one notable advantage – unobtrusive urban advertising – it is rather a symptom of absence of aggressive market competition than a merit of the army of designers. Despite all the efforts of authorities in the field of ideological creativity, the style of Belarusian political regime (in the aesthetic sense) hasn’t taken shape over the years. Therefore, there is no need to talk about the country of decorators and rapid development of design in Belarus. Of course, this is partly due to the fact that intelligentsia, as well as authorities, has rural roots (that’s why there is such a piety for nature and rural aesthetics), and only learns to be urban. The initial capital accumulation, provincialism and peculiarities of historical development of Belarus have produced an eclectic narrow-minded culture and the phenomenon of the lumpen-elite.

Quiet partisan life

During two thousandth years the repressive governmental policy has increased, many of those who remember the 1990s experience an unpleasant feeling of deja vu. The authorities’ attempts to revive the Soviet administrative practices instigate new dissidence. Rebellion is easily emerging under despotism, but it is still too early to talk about the culture of rebellion as a system in Belarusian situation – only a couple of notable examples of individual artists’ rebellion can be named. Perhaps, Ales Pushkin’s performance “A Gift to the President” is a proverbial example of Belarusian action art: the artist dumped a wheelbarrow of manure to the presidential palace and pierced with pitchforks the portrait of Lukashenko. Now, however, Pushkin doesn’t accomplish such aggressive actions, because of regular arrests and beatings he has chosen a different strategy: the artist works in his village and lets the local government know beforehand about his upcoming actions and their content. For the fellow villagers’ surprise such action art is an example of tactics of private situationism.

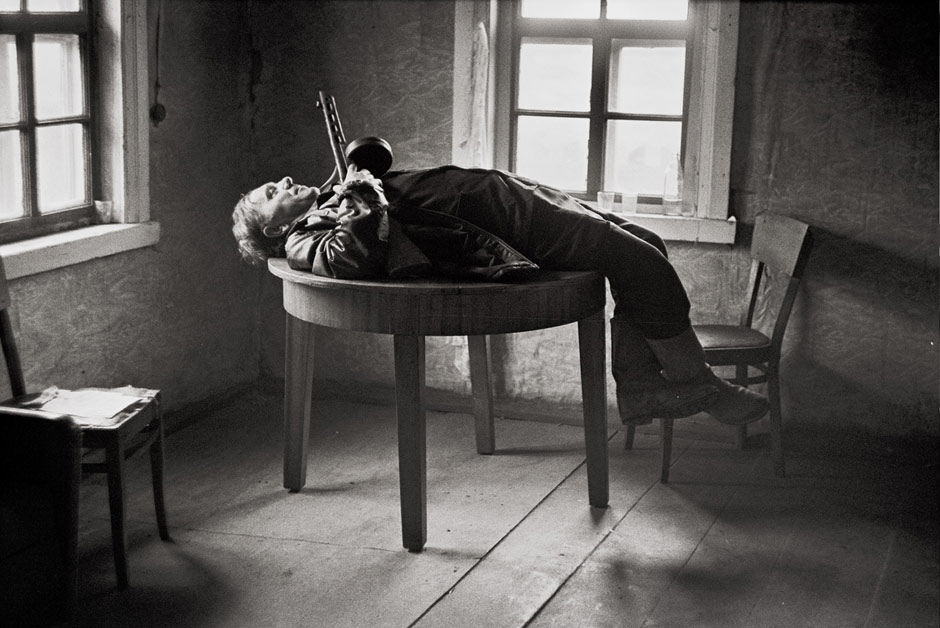

Igor Tishin:

Easy Partisan Movement,

1997

Easy Partisan Movement,

1997

Ales Pushkin’s example is demonstrative – in Belarus art rebellion is expressed in the internal individualist resistance. It reminds partisan tactics, but this is guerilla warfare without open battles – quiet partisan life imperceptibly flowing across the official culture. The image of partisan is popular both in the official and independent Belarusian culture. But while in the official culture partisans are romantic heroes, whose image is endlessly disseminated in the Belarusian cinema and television for patriotic prevention, guerilla warfare became a survival strategy in the informal culture. In the late 90′s an artist Igor Tishin created a project entitled “Easy Partisan Movement”, representing “unbearable light being” of Belarusian partisans. And in my opinion this is a perfect illustration of the 2000s: not only artists have learned to live in that way, quietly working in their workshops and selling their works abroad, but also many cultural officials, who understand the situation and latently criticize it, but perfectly “camouflaged” on the state system. Despite the absence of open conflict, guerilla warfare always implies resistance, and, of course, the basis of the general discontent is the criticism of the regime and its official ideology.

“Partisan culture” was very popular and had influenced the poetics of Belarusian 2000s. Practically the only independent magazine about the contemporary Belarusian culture is called “pARTisan”. In its first issue, published in 2002, its editor, an artist Arthur Klinov presented a manifesto “Partisan and Anti-partisan” where he formulated the basic concept of guerilla warfare: “The concept of partisan is the concept of struggle, a person’s struggle for the right of individual cultural autonomy, but only when this right is also recognized for another person.” The strategy of guerrilla warfare was endowed with features of new avant-garde, which, in fact, didn’t become reality due to the rollback of modernist ideas. The PARTISAN magazine and the culture which the magazine writes about, were, roughly speaking, tautological romanticism of the underground, nostalgia for the “big gesture” of modernism.

In this context, the activity of the legendary gallery “The Underground” is very demonstrative. It was opened in the basement of one of the Soviet buildings in the center of Minsk in May 2004 and had been existed until April 2009. The gallery exhibited practically all informal Belarusian artists (sometimes exhibitions changed every day). The audience constantly asked “don’t you worry?” or “is it allowed?”. The gallery was a parallel world where the things forbidden by the official culture existed: presentations of banned books, banned music concerts, exhibitions of the artists not allowed to exhibit anywhere else. But in reality, romantization of the underground did not lead to overcoming nostalgic dependence and consolidation of powers in some meaningful post avant-garde movement.

Artur Klinov:

Partisan’s Boutique Transportable,

2003

Partisan’s Boutique Transportable,

2003

However the partisan strategy proved to be very viable. There was no persecution by authorities – the official culture ignored timid manifestations of the informal stage. Artists aesthetisized guerilla warfare, sometimes turning it into exotic goods to the West. A good example is the “Partisan’s Boutique” by Arthur Klinov. The artist travels around Europe and sells to foreigners various products with the Soviet nostalgic character. Klinov publishes PARTISAN and delivers excursions to Minsk, which, according to him, looks like a city-preserve, Disneyland of Soviet utopia. Klinov’s Partisan Empire turned into a nostalgic attraction that has begun to pay dividends.

***

Of course, in Belarus, unlike Russia and Ukraine, there are no oligarchs – all the big money is concentrated in the authorities’ and their supporters’ hands, who see contemporary art as a threat and an irritant. With increasing of the state’s ideological influence (ideology lessons were included into the school program, while arts were removed) the tactics of guerilla warfare is replaced by activism practice, the politicization of art and its production occurs. By the end of the two thousands Belarusian art has gradually activated: the Gallery of contemporary art “Ў” (the only independent art center) was opened in 2009, the portal about contemporary Belarusian art began to operate, some notable Belarusian exhibitions were held abroad (on the initiative of foreign curators and institutions), and this year Belarus for the first time took part in the Venice Biennale. Today we see that artists’ and critics’ activity are growing, and in my thought there is a new stage of rethinking of Eastern European art.

Of course, in Belarus, unlike Russia and Ukraine, there are no oligarchs – all the big money is concentrated in the authorities’ and their supporters’ hands, who see contemporary art as a threat and an irritant. With increasing of the state’s ideological influence (ideology lessons were included into the school program, while arts were removed) the tactics of guerilla warfare is replaced by activism practice, the politicization of art and its production occurs. By the end of the two thousands Belarusian art has gradually activated: the Gallery of contemporary art “Ў” (the only independent art center) was opened in 2009, the portal about contemporary Belarusian art began to operate, some notable Belarusian exhibitions were held abroad (on the initiative of foreign curators and institutions), and this year Belarus for the first time took part in the Venice Biennale. Today we see that artists’ and critics’ activity are growing, and in my thought there is a new stage of rethinking of Eastern European art.

REVISION group

(Maxim Vakulchik,

Jane Grak,

Andrei Dureiko,

Andrei Loginov,

Maxim Tyminko),

REVISION project,

2005

(Maxim Vakulchik,

Jane Grak,

Andrei Dureiko,

Andrei Loginov,

Maxim Tyminko),

REVISION project,

2005

Within a decade, a whole army of artists, who have left Belarus to study abroad, not only finally got used to new conditions, but also have got excellent European education. Many of them attended classes of famous contemporary artists – Martha Rosler, Daniel Buren, Gerhard Merz, and others. Artists, who are ready to represent Belarus at the professional international level, have begun actively exhibit. The external difference of the Belarusians’ creative ways of work, those who have studied in Europe, and those who live and work in Belarus, has already manifested itself in collaborative exhibitions. The works by those who stay in Belarus appear to be too hermetic and follow the traditions of “the poor art”, while the works of the emigrants are more spectacular and expensive in manufacture. Today collaborative exhibitions are extremely important for the resumption of contact between artists and have a great influence on the development of art in general.

In the 2000s the institutes of criticism and curatorship continue to be at a nascent stage. On the one hand, the Belarusian critical school is characterized by the eternal problem of self-identification and isolationist pathos, and on the other hand, it is characterized by the destructive self-criticism against the background of provincialism complex. However, in recent years, philosophers, sociologists, and art critics who possess the latest knowledge and new critical tools emerge (and many of them graduated from the European Humanities University). In the 2000s Belarusian art has began to regenerate: there are young professionals, appropriation of European art paradigm, new disciplines and a new understanding of the role of cultural institutions. Belarusian art entered the second decade with a renewed hope; it is ready not only for predictions about the prospects of its development, but also for articulation of its own demands.

©

Moscow Art Magazine